Fusion and Runtime Compilation for NNVM and TinyFlow

Fusion and Runtime Compilation

Today’s deep learning models perform tens of thousands of operations on GPU. The input and output of each GPU kernel has to be stored in the global memory, but read and write on global memory is much slower than on on-chip register. When some special kernels executed in sequence share some data, performance and memory locality can be improved by fusing these kernels into a single, larger one, operating on on-chip register instead of global memory.

For example, computing add(mul(x0, x1), x2) is usually with two separate kernels:

extern "C" __global__ mul_kernel (uint32_t num_element,

float *x0, float *x1, float *y) {

int global_idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (global_idx < num_element)

y[global_idx] = x0[global_idx] * x1[global_idx];

}

extern "C" __global__ add_kernel (uint32_t num_element,

float *x0, float *x1, float *y) {

int global_idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (global_idx < num_element)

y[global_idx] = x0[global_idx] + x1[global_idx];

}

__host__ compute(uint32_t num_element, float *x0,

float *x1, float *x2, float *y) {

float *tmp = malloc(num_element * sizeof(float));

mul_kernel(x0, x1, tmp);

add_kernel(tmp, x2, y);

}

However, if this pattern occurs often enough, the two kernels can be fused into one. The net result is reduction of reads/writes to global memory as well as memory allocation for temporary variables:

__host__ compute_with_fusion(uint32_t num_element,

float *x0, float *x1, float *x2, float *y) {

fusion_kernel(num_elment, x0, x1, x2, y);

}

But, there is no straightforward answer to the question of “to fuse or not to fuse”. The number of possible kernel combinations is exponential; preparing a pool of fused kernels statically is impractical and expensive. We opt to automatically generate fusion kernel code during runtime when the symbolic graph is available. Consequently, we also compile the generated kernel code during runtime.

This feature is especially useful when users write customized operators, such as customized optimization function and updaters. It is worth mentioning this feature is available in Theano, which pioneers many ideas in the deep learning system. Our goal is to build it with a modular approach so that the optimization module can be reused across multiple deep learning frameworks.

Implement Fusion and RTC in NNVM

NNVM is a modular, decentralized and lightweight framework to help build deep learning libraries. It provides ways to construct, represent and transform generic computation graphs irrespective and independent of how it is executed. Its goal is to be a high level intermediate representation library for neural nets and computation graphs generation and optimization.

More concretely, NNVM allows user to register operators and their attributes, leading to the possibility of having multiple reusable optimizations, like the following code:

// attributes can be registered from multiple places.

NNVM_REGISTER_OP(add)

.describe("add two data together")

.set_num_inputs(2);

using FGradient = std::function<std::vector<NodeEntry>(

const NodePtr& nodeptr,

const std::vector<NodeEntry>& out_grads)>;

// register the function for generating the backward graph of the node

NNVM_REGISTER_OP(add)

.set_attr<FGradient>(

"FGradient", [](const NodePtr& n,

const std::vector<NodeEntry>& ograds){

return std::vector<NodeEntry>{ograds[0], ograds[0]};

});

Rich information about the operators affords optimizations on the computation graph. In NNVM, a pass is a process that takes an existing graph with its current attributes, enriches it with more attributes, or transforms to yet another computationally equivalent graph. Notably, symbolic differentiation, memory planning, shape/type inference are all implemented as passes.

// A Pass is an "Operator on Graph".

// It takes a source graph and return a graph that may or may

// not be the same as the input one. A pass can generating a

// new Graph, or add new attributes to the graph.

Typedef std::function<Graph (Graph src)> Pass;

// Apply a series of pass transformations on the input graph.

Graph ApplyPasses(Graph src, const std::vector<std::string>& passes);

// Apply one pass to the graph.

Graph ApplyPasses(Graph src, const std::string& pass);

Implementation

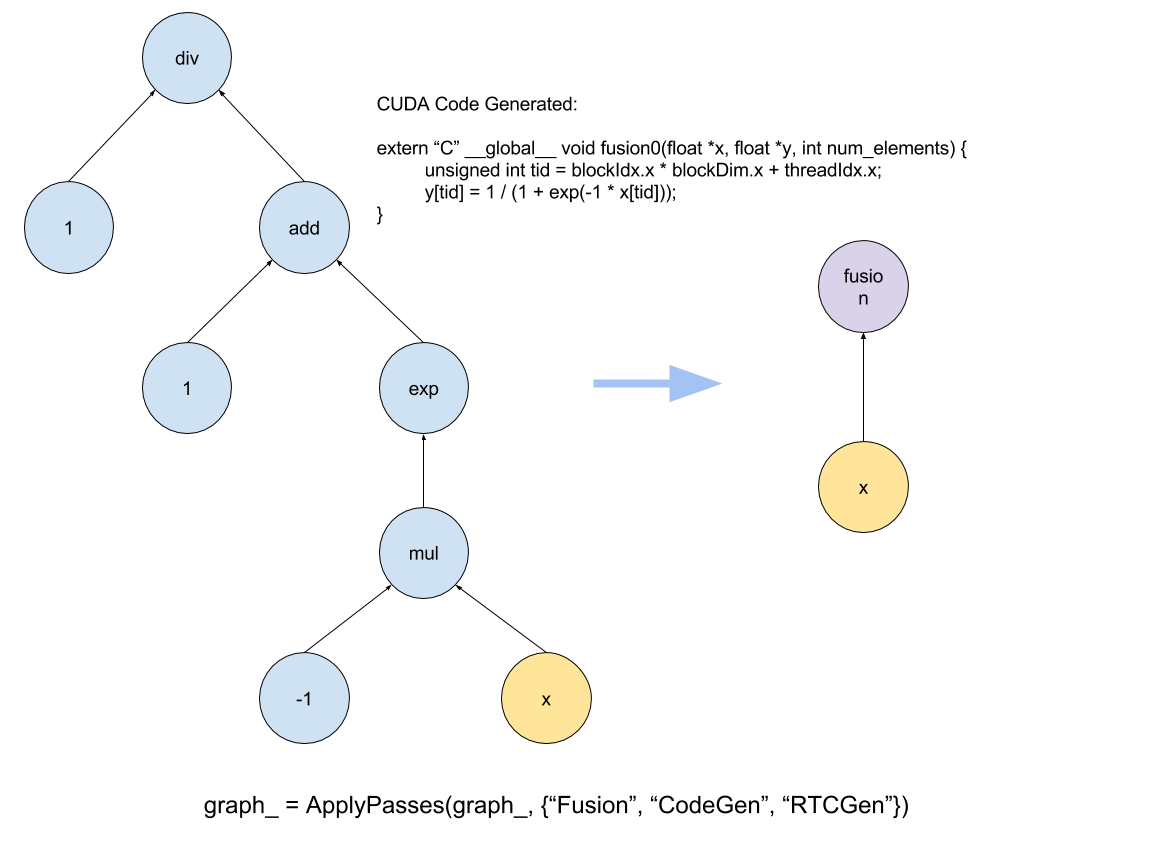

Following the abstract provided by NNVM, kernel fusion include three passes on the symbolic graph: “Fusion”, “CodeGen”, “RTCGen”.

In the fusion apart NNVM performs a traversal on the original graph, from outputs to inputs, by DFS(depth-first-search). When it detects some pattern can be fused, for instance if the current node and some children nodes are element-wise operations, it replaces them with one fused node. It also builds a mapping from the fusion node to the subgraph, in preparation for code generation.

// pseudo-code for fusion pass

Graph Fusion(Graph src) {

std::unordered_map<Node, SubGraph> node_to_subgraph_map;

DFSVisit(graph, [](Node node) {

// for each nodes in the graph

if (IsFusible(node)) {

// get the subgraph which can be fused

SubGraph subgraph = DetectFusibleSubGraph(node);

// fuse them into one fusion node

Node fusion_node = Fuse(subgraph);

// replace the origin subgraph with the fusion node

ReplaceWithFusionNode(subgraph, fusion_node);

// build a mapping from the fusion node to the subgraph

node_to_subgraph_map[fusion_node] = subgraph;

}

});

// bind the map to the returned graph for the following code generation

Graph ret;

ret.attrs["subgraph"] = std::make_shared<any>(std::move(node_to_subgraph_map));

// return the map after fusion

return ret;

}

The fusion pass generates a new graph, with the fused nodes replacing the subgraphs they represent, as well as the mapping between them.

In order to do code generation, we need to know how to generate its CUDA code for every node in the subgraph. For instance, for add node, we need to generate “+” string for it. We define a series of basic AST(Abstract Syntax Tree) class for this purpose. Part of definitions are listed below:

/*! \brief base class for all ast nodes */

class AST {

public:

virtual ~AST() {}

virtual std::string CodeGen() = 0;

};

/*! \brief AST class for float literals like "1.0" */

class FloatAST : public AST {

public:

FloatAST(float val)

: val_(val) {}

inline std::string CodeGen() override {

return "float(" + std::to_string(val_) + ")";

}

private:

float val_;

};

/*! \brief AST class for referencing a variable, like "a" */

class VariableAST : public AST {

public:

VariableAST(std::string name)

: name_(name) {}

inline std::string CodeGen() override {

return name_;

}

private:

std::string name_;

};

/*! \brief AST class for a binary operator */

class BinaryAST : public AST {

public:

BinaryAST(char op, ASTPtr lhs, ASTPtr rhs)

: op_(op), lhs_(lhs), rhs_(rhs) {}

inline std::string CodeGen() override {

return "(" + lhs_->CodeGen() + " " + op_ + " " + rhs_->CodeGen() + ")";

}

private:

char op_;

ASTPtr lhs_, rhs_;

};

inline ASTPtr operator+(ASTPtr lhs, ASTPtr rhs) {

return ASTPtr(new BinaryAST('+', lhs, rhs));

}

inline ASTPtr operator*(ASTPtr lhs, ASTPtr rhs) {

return ASTPtr(new BinaryAST('*', lhs, rhs));

}

As shown above, naive ASTs can be composed to represent more complicated code structure. We register an attribute named FCodeGen for every element-wise operation which takes current node itself and the input ASTs and returns the output ASTs, in order to express the composition procedure between the inputs of this operation. As an example:

NNVM_REGISTER_OP(__add_symbol__)

.set_attr<FCodeGen>(

"FCodeGen", [](const NodePtr& n,

const std::vector<ASTPtr>& inputs) {

return std::vector<ASTPtr>{

inputs[0] + inputs[1],

};

});

After these preparation, we just need to take the graph after fusion, get the subgraphs by fusion nodes and the mirror mapping, then use the FCodeGen attribute of each node in the subgraph to generate the CUDA code we want. Add it as a graph attribute and register a new pass called “CodeGen”.

// pseudo-code for code generation pass

Graph CodeGen(Graph ret) {

// we define kernel as a pair of function name and function body

using std::pair<std::string, std::string> Kernel;

std::unordered_map<Node, Kernel> node_to_kernel_map;

// get the map we bind before from the graph

std::unordered_map<Node, SubGraph> node_to_subgraph_map =

&ret.GetAttr<std::unordered_map<Node, SubGraph>>("subgraph");

// traverse the map, generate the kernel from subgraph one by one.

for (std::pair<Node, SubGraph> kv: node_to_kernel_map) {

// generate ast from subgraph

AST ast = GenAST(kv.second);

// generate real cuda code from ast

Kernel kernel = GenKernel(ast);

// build a mapping from node to the kernel code.

node_to_kernel_map[kv.first] = kernel;

}

// bind the map to the returned graph for the following rtc generation

ret.attrs["kernel"] = std::make_shared<any>(std::move(node_to_kernel_map));

return ret;

}

The next task is easy: just compiles the generated CUDA code in the runtime. We choose to use NVRTC library, which accepts CUDA C++ source code in character string form and creates handles that can be used to obtain the PTX. The PTX string generated by NVRTC can be loaded and linked with other modules by the CUDA Driver API, then we can call the compiled kernel by cuLaunchKernel.

// pseudo-code for rtc generation pass

Graph RTCGen(Graph ret) {

std::unordered_map<Node, RTC> node_to_rtc_map;

// get the map we bind before from the graph

std::unordered_map<Node, Kernel> node_to_kernel_map =

&(ret.GetAttr<std::unordered_map<Node, Kernel>>("kernel"));

for (std::pair<Node, Kernel> kv: node_to_kernel_map) {

// generate rtc from kernel with our predefined rtc class

RTC rtc = RTC(kv.second);

// build a mapping from node to the rtc

node_to_rtc_map[kv.first] = rtc;

}

// bind the map to the returned graph

ret.attrs["rtc"] = std::make_shared<any>(std::move(node_to_rtc_map));

return ret;

}

Then we register these three passes into NNVM (in three separate source files actually) :

NNVM_REGISTER_PASS(Fusion)

.describe("fuse multiple kernels into one")

.set_body(Fusion)

.set_change_graph(true)

.provide_graph_attr("subgraph");

NNVM_REGISTER_PASS(CodeGen)

.describe("generate CUDA code from subgraph")

.set_body(CodeGen)

.set_change_graph(true)

.depend_graph_attr("subgraph")

.provide_graph_attr("kernel");

NNVM_REGISTER_PASS(RTCGen)

.describe("generate RTC from kernel code")

.set_body(RTCGen)

.set_change_graph(true)

.depend_graph_attr("kernel")

.provide_graph_attr("rtc");

Now we’ve create three passes for NNVM! After we get the symbolic graph, we just need to do ApplyPass(graph, {"Fusion", "CodeGen", “RTCGen”}) on the original graph, then a new graph with some patterns fused and CUDA kernels generated.

Test Out The Implementation in TinyFlow

We use TinyFlow as a test case to demonstrate how this can be applied to a new deep learning framework. TinyFlow is a showcase to demonstrate how to use NNVM to build a clean, minimum and powerful computation graph-based deep learning system with same API as TensorFlow. The whole system is only 2K lines of code with CPU and GPU support.

The original TinyFlow utilizes Torch for its operator backend. In this blog, we will explore how to add fusion and RTC features on TinyFlow, alongside with the Torch-backend

Example 1: Customized Activation Function

Let us take an example, say you want to create a new activation operation. For the time being we assume it is a sigmoid: sigmoid(x) = 1 / (1 + exp(-x)), we can create it by existing tf.exp operation in TinyFlow like

def my_sigmoid(x):

return 1 / (1 + tf.exp(-x))

After we apply Fusion & CodeGen & RTCGen passes on the graph, we can use this operator with compiled kernel just like the native operators.

The point is, user likes to write simple and intuitive operations. We call them imperative operations, which express the exact steps of computation. However, they can be slow. With fusion and RTC, we can retain the expressiveness while achieving the same level of efficiency of a big op.

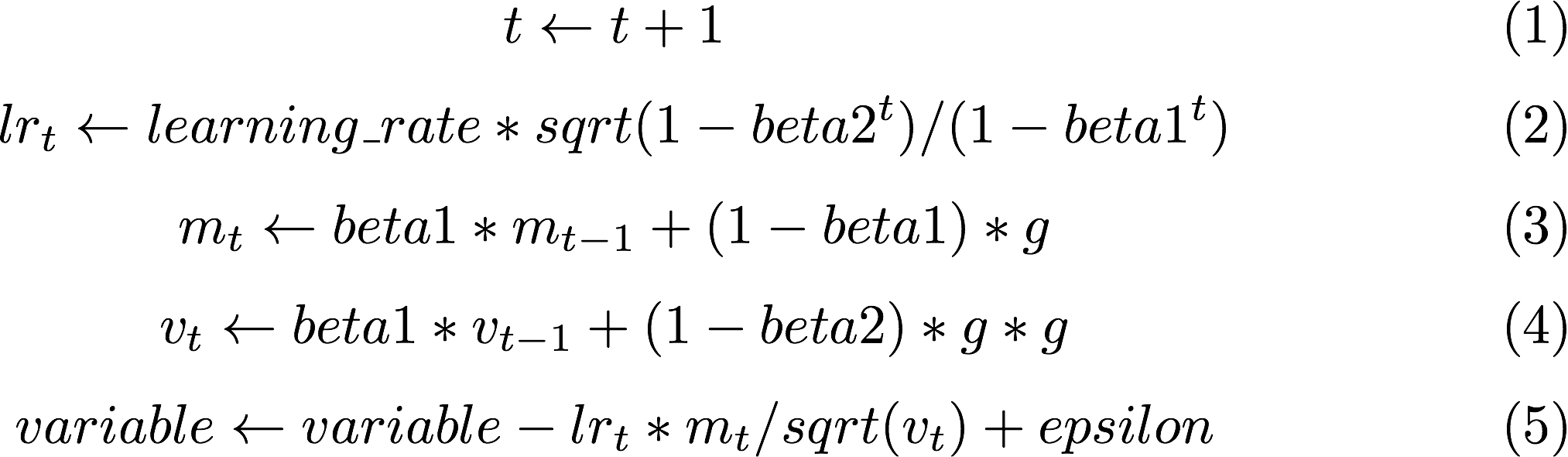

Example 2: Quick Compilation of Optimization Rules Runtime Compiled Adam

Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) is another method that computes adaptive learning rates for each parameter. In addition to storing an exponentially decaying average of past squared gradients, Adam also keeps an exponentially decaying average of past gradients, similar to momentum, and the update rule for variable with gradient is described as below:

Tinyflow Implementation as below:

from nnvm import symbol as _sym

class AdamOptimizer(object):

def __init__(self, learning_rate=0.001, beta1=0.9, beta2=0.999, epsilon=1e-04, name='Adam'):

self.name = name

self.t = _base.Variable(_sym.zeros(shape=[1]), name+'_t')

self.lr = learning_rate

self.beta1 = beta1

self.beta2 = beta2

self.epsilon = epsilon

self.m = []

self.v = []

def minimize(self, obj):

variables = obj.list_input_variables()

grads = _base.gradients(obj, variables)

updates = []

for i, v in enumerate(variables):

self.m.append(_base.Variable(_sym.zeros_like(v), self.name + '_m' + str(i)))

self.v.append(_base.Variable(_sym.zeros_like(v), self.name + '_v' + str(i)))

update_t = _sym.assign(self.t, self.t + 1)

rate = _sym.sqrt(1 - self.beta2 ** update_t) / (1 - self.beta1 ** update_t)

lr_t = self.lr * rate

for var, g, m, v in zip(variables, grads, self.m, self.v):

update_m = _sym.assign(m, self.beta1 * m + (1 - self.beta1) * g)

update_v = _sym.assign(v, self.beta2 * v + (1 - self.beta2) * g * g)

update_var = _sym.assign(var,

var - lr_t * update_m / (_sym.sqrt(update_v) + self.epsilon))

updates.append(update_var)

return _base.group(*updates)

As you can see, there many element-wise operations in the update rules that can be fused as one big operator easily, and we expected that the performance will gain a boost by our optimization.

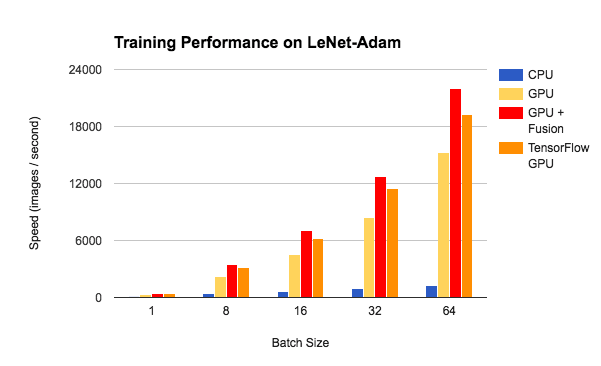

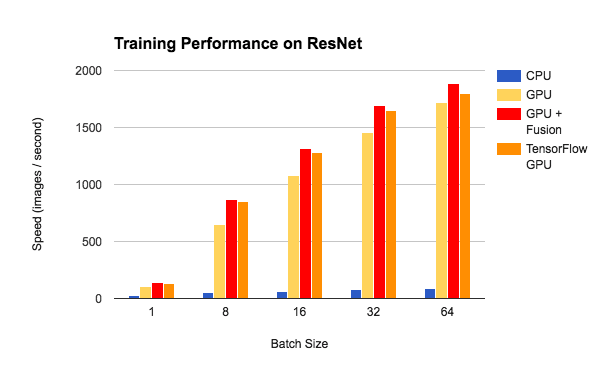

Benchmark

we have done some benchmark tests of the training performance on LeNet and ResNet. We compared the training speed between CPU, GPU and GPU with NNVM-Fusion. It demonstrates that NNVM-Fusion can improve the GPU training performance by 1.4x-1.5x on LeNet and 1.1x-1.3x on ResNet with medium batch size. We also compared the training speed with the same model on TensorFlow. With NNVM-Fusion, TinyFlow’s performance is on par with TensorFlow on ResNet, and better on LeNet.

Future Works

There still are lots of work to do in the future, like the AST class should be enriched to express more structure, and more types of fusion pattern can be explored, like combination of conv, bn and relu. Also, it’s important to reduce the analysis overhead during detect fusible patterns. Can we design a caching mechanism to store the pattern or subgraph we have seen before? And so on. As we have said before, due to the fact that this optimization is built upon NNVM, it should be easily reusable on many platforms. In order to prove this, we will apply this module into MXNet as a plugin of NNVM next, and we also believe that we will discover more interesting ways to improve and extend this module during this procedure.

Show Me the Code

- All the code can be found in NNVM-Fusion at https://github.com/dmlc/nnvm-fusion

- You can also checkout the code of NNVM at https://github.com/dmlc/nnvm

- We choose TinyFlow(https://github.com/tqchen/tinyflow) as the experimental platform, and it only requires 220 lines code for embedding this feature.

Acknowledgements

The author has many thanks to Tianqi Chen, Mu Li, Minjie Wang and Prof. Zheng Zhang for their helpful advices on the implementation and documentation of NNVM-Fusion.

Bio

NNVM-Fusion is contributed by Ziheng.

Ziheng is an undergraduate student in Computer Science at Fudan NLP lab, this work is done when he works as a research intern at New York University Shanghai.